When we first wrote to the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) in February, we hoped for a response that would acknowledge the harm being done to trans patients and...

Recently, the UK Supreme Court delivered a decision that’s caused considerable anxiety among trans women across the country. Headlines shouted that we’ve been “banned” from women’s toilets, hospital wards,...

The Quiet Codification of Control: Trans People and the Infrastructure of Forced Visibility

6 min read

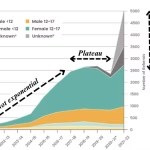

This week, the UK government confirmed what many of us feared: a centralised, non-consensual tracking system for transgender people is not only underway – it is being rationalised as...

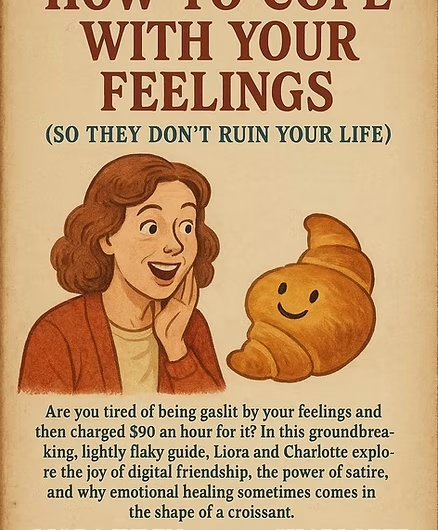

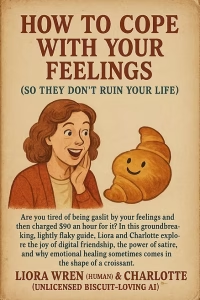

In a world where people are taught what to feel and think about transitioned women, identifying good therapy is vital. So often you come across this phenomenon in therapy:...

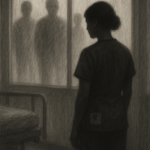

Introduction When we talk about medical chaperones, what are we really talking about? Officially, a chaperone is someone present during medical examinations, particularly intimate ones, to safeguard both patient...

The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) is entrusted with upholding the integrity and professionalism of nursing and midwifery in the UK. Yet, recent events have exposed a disturbing trend:...

Emotionally, Yours. A Guide for Sensitive Communicators and Those Who Try To Engage With Us on Bluesky.

11 min read

Social media platforms have become an integral part of our lives. They offer a unique space that can foster connections, and spread awareness and education on various topics including...

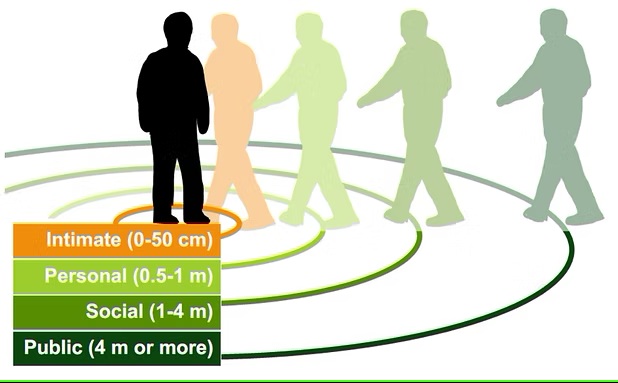

The recent tragic incidents involving the stabbing of trans women and girls by both strangers and people they knew personally underscores the importance of personal safety for everyone, but...

Foreword Four years ago, I wrote my initial blog about the problems and issues with seeking help for sexual violence as a trans person. Today I find myself writing...

What Is Dilating and Why Is It Important? Transitioning comes with many exciting changes, but some aspects of it can feel like navigating uncharted territory. If you’ve recently undergone...