When we first wrote to the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) in February, we hoped for a response that would acknowledge the harm being done to trans patients and healthcare workers. The letter was clear, direct, and rooted in the NMC’s own Code of Conduct. It outlined how gender-critical activists were weaponising the nursing profession to dehumanise trans people: misgendering them publicly, outing them without consent, and fostering a culture of hostility within healthcare spaces. We had hoped that the NMC might condemn these actions as violations of their ethical duties. Instead, they replied with a carefully worded statement that, while technically compliant, avoided addressing the systemic harm at its core.

The NMC’s response begins by acknowledging “the importance of hearing about people’s experiences,” which is not entirely untrue. They emphasise their commitment to equality and non-discrimination, stating: “We are clear on our stance that there is no room for discrimination, bullying or harassment of any kind towards anyone in the health and care sector.” These words align with the principles I outlined in my letter, which stressed the NMC’s responsibility to “uphold the reputation of the profession” (Clause 20.1) and ensure “safe, compassionate, equitable care” for all patients (Clause 16.1).

However, this commitment is not matched by action. The NMC’s reply focuses on policy frameworks – freedom of expression guidelines, case studies of disciplinary actions, and education standards, but it fails to acknowledge the specific allegations we raised. For instance, they mention examples like a nurse who “persistently makes comments to [a trans colleague] about ‘accepting the body they are in’” or a nurse who “deliberately misgenders a transgender person.” These cases are framed as isolated incidents of harassment, not as part of a broader pattern of ideological hostility. The NMC’s language suggests that their role is to address individual violations of the Code, but it does not acknowledge the systemic weaponisation of professional authority by a collective of gender-critical nurses.

This omission is glaring. In my letter, I wrote: “The silence of the NMC in the face of this growing hostility is not neutrality; it is complicity.” Yet the NMC’s response never directly addresses this claim. Instead, they frame their role as “hearing people’s experiences” and “ensuring professionals are non-discriminatory,” which feels like a passive acknowledgment rather than an active condemnation of harm. They avoid explicitly stating that gender-critical nurses’ actions: such as using uniforms to promote transphobic ideologies in the press, are violations of the Code.

The NMC fails to engage with the specific issue of forced outing, which I emphasised as a critical violation of privacy and dignity. The Code’s Clause 5 states: “You must respect the confidentiality of information about people in your care.” Forced outing, which exposes a trans person’s gender history without consent, directly contradicts this principle. Yet the NMC’s response does not mention this at all. Instead, they focus on “inappropriate expression” of beliefs, such as harassment or misgendering in clinical settings, but they do not condemn the misuse of professional authority to incite public hostility.

The result is a response that feels like a reassurance rather than a commitment to action. The NMC’s language is neutralising, phrases like “we are clear on our stance” and “there is no room for discrimination” sound aspirational but lack concrete measures to address the real-world consequences of their inaction. For trans nurses and patients, this silence sends a message: “Your safety and dignity are not priorities.”

This gap between the NMC’s stated values and their actual response is deeply troubling. When institutions fail to protect vulnerable communities, they risk perpetuating harm. The Supreme Court ruling that trans women are not “women” has already legitimised anti-trans hostility in public discourse, but the NMC’s failure to address systemic issues within healthcare exacerbates this crisis. Fear and exclusion are not just abstract concepts – they are lived realities with extensive impact on health.

The NMC’s response is not just inadequate; they have confirmed that it is complicit. By evading direct engagement with the weaponisation of nursing professionalism and the harm caused by forced outing, they leave trans people to navigate a healthcare system where their safety is repeatedly compromised. This silence is not neutrality, it is an endorsement of the very hostility that threatens our lives.

As I write this blog, I am reminded of the words from my original letter: “The future of nursing depends on your actions.” The NMC must decide whether to uphold its ethical duties or continue enabling harm. For trans women in healthcare, their response is not just a regulatory issue, it is a matter of survival.

No condemnation of forced outing.

The most glaring omission was their silence on forced outing: the deliberate exposure of a trans person’s gender history without consent. This is not merely an ethical breach, it is a violation of privacy, trust, and dignity. Yet the NMC’s response omits this issue entirely, leaving trans nurses and patients to navigate a landscape where their safety and autonomy are dangerously undermined.

Forced outing is the act of publicly revealing a trans person’s gender history or identity without their consent. It is not a “personal belief” or an ideological debate, it is a concrete violation of privacy, confidentiality, and human rights. It is not something that could affect cisgender, heterosexual people, whose lives have not been historically policed with the violence all too present in trans women’s lives. For transitioned women, this violence is neither abstract, nor theoretical. In the Galop transphobic hate crime report (2020), 5 years ago when tensions were arguably less intense, 4 in 5 trans people experienced some hate-crime in the previous 12 months, 1 in 4 experienced a physical assault or threat and nearly 1 in 5 experienced a sexual assault or threat. 70 % said hate crime harmed their mental health and 55 % felt less able to leave home.

Forced outing causes immediate emotional and psychological distress, causing a sense of betrayal by trusted professionals. Publicity surrounding transitioned women identifies them as a target, which can lead to intense anxiety, depression, and further traumatic experiences. Transitioned women feel a loss of personal autonomy, a loss of control, and a loss of safety. Outing can expose trans people to targeted harassment, hate crimes, and workplace hostility. For trans healthcare workers, this creates a hostile environment that enforces an intolerable culture which encourages them to leave the profession entirely.

If nurses are seen as enforcers of exclusionary ideologies rather than healers, the entire nursing community loses credibility. When nurses use their uniforms, titles, or professional standing to promote transphobic ideologies -whether in media, social media, or within healthcare settings, they are not merely expressing personal beliefs. They are leveraging institutional trust to harm marginalised communities. This is a direct betrayal of the NMC’s duty to “promote professionalism and trust” (Clause 20). It creates a culture where trans people are seen as threats rather than people with human rights and dignity, and where discrimination is normalised under the guise of “professionalism.”

The NMC’s failure to address forced outing is not neutrality: it is complicity. By refusing to condemn or investigate these actions, they implicitly endorse a system where trans people are silenced, exposed, and excluded. Their response, which focuses on “individual cases” rather than systemic harm, leaves trans nurses and patients vulnerable to ongoing violence against us.

We discussed the NMC’s response with one of our trans members who is a registrant. This is what that silence feels like, in the words of one of our own::

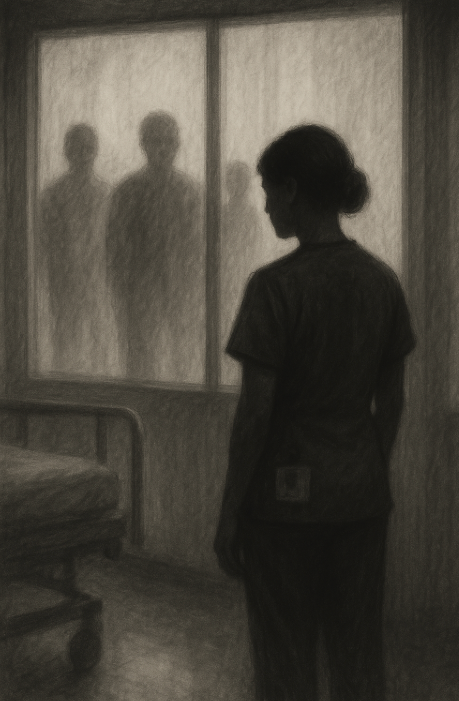

“It has never been easy as a transitioned woman at work, even before the Supreme Court ruling. I’ve always tried to make myself as small as possible: changing in the staff room when no one was around, and hiding out of view when I just need to cry about how awful things are becoming. But now? Now it’s intolerable. I’m having to hide all the time. I use toilets away from my workplace, sometimes even outside the grounds, just to cope. And my trust in others is suffering, I’m terrified of my colleagues – every glance, every whisper feels like a threat – people who I previously felt safe with. Nothing feels safe anymore. When I’m at work, I should be focused on my patients, but instead, I’m constantly worrying about standing outside the disabled loo, wondering who might recognise me or what gossip might spread among my colleagues. And I’m terrified of ending up in the press: even when I’m super careful, because you don’t know what they [gender-critical nurses] are going to do next. This has taken a devastating toll on my mental health. I’ve been really unwell recently, so much so that I’ve needed care myself. It’s not just about being trans; it’s about being a nurse and feeling like I can no longer exist in the very profession I chose to serve others. I’m constantly asking: Why is this happening? Why are we being treated like threats instead of patients or colleagues? Why does the NMC say they’re against discrimination, but their silence lets this continue?”

The Supreme Court ruling has not just invalidated our identities, it has legitimised gender-critical hostility in professions where trans people are already vulnerable. Nursing, midwifery, and other female-dominated fields have long been spaces where cisgender women dominate, but now the NMC sends its own chilling message: complicity.

This isn’t just about legal definitions – it’s about power. It reinforces the idea that trans women are not “real” women, and therefore not entitled to the same rights or safety or privacy in spaces like hospitals, wards, or even toilets. For trans healthcare workers, this creates a sense of being “policed” – constantly under surveillance by cisgender colleagues who may view us as outsiders, threats, or “infiltrators.”

The NMC’s response only makes things worse. By focusing on overt misgendering and individual cases, they imply that only visible acts of discrimination matter. But what about the subtler, more destructive behaviors? The quiet hostility in workplaces, the unspoken rules that exclude us, the fear of being outed or targeted by colleagues who don’t see us as human?

The NMC’s reply says: “We’ll only protect you from overt misgendering.” But it leaves deeper, more insidious harms unchecked. It sends a chilling message to trans workers: you’re fair game.

This isn’t just about one ruling or one council. It’s about a system that continues to marginalise us within the medical profession. Trans nurses and midwives are people: they are caregivers, healers, and advocates. But if they can’t exist safely in healthcare spaces, how can we expect trans patients to receive appropriate, dignified care?

The wider issues are compounding.

When trans nurses are forced into silence or fear, it sends a devastating message to trans patients: “You may not be safe here.” It erodes trust in the profession and in healthcare system itself. Patients who already face barriers, like trans individuals but also other minorities, will avoid care entirely if they believe their dignity will be violated. For example, a trans person might skip a routine check-up or delay treatment for fear of being mistreated, outed, othered, or harassed by staff.

The NMC’s failure to address systemic issues like forced outing and ideological hostility undermines the very principles it claims to uphold. The NHS Constitution is clear: “The NHS must treat people as individuals… and respect their dignity and rights.” But when institutions like the NMC fail to act, this promise is a hollow one.

Gender-critical ideology has not only infiltrated healthcare but has captured key institutions including the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC), and government ministries. These bodies, which are meant to protect vulnerable communities, have instead become platforms for legitimising harm.

This is not accidental, it’s a strategic capture of institutions by activists who frame their ideology as “protecting women” or “upholding professional standards.” By embedding themselves in regulatory frameworks, gender-critical advocates have created a self-reinforcing cycle:

- Institutional legitimacy: Their views are presented as “neutral” or “evidence-based,” even when they contradict clinical and human rights principles.

- Policy influence: Decisions like the Supreme Court ruling on trans women’s place in the Equality Act, the EHRC’s over-reach and the NMC’s indifference are weaponised in key areas, designed to mark transitioned women for abuse and perpetuate exclusion from society.

- Public perception: When institutions fail to condemn anti-trans behavior, it reinforces the idea that such hostility is acceptable or even “necessary.”

The NMC’s failure to act is not just about policy, it’s about people’s lives. When institutions like the NMC fail to protect trans healthcare workers, they also fail to protect patients who depend on them. The Supreme Court ruling and gender-critical ideology have created a crisis that demands urgent action, but without accountability from regulatory bodies, the harm will continue.

This blog is part of a larger series fighting for dignity, safety, and equity in healthcare for transitioned women.

27/12/2025 Editor’s note: This piece was written following the NMC’s initial response to our February correspondence. Subsequent evidence of harm has since been formally documented and shared with the NMC in further regulatory submissions.